By Micah Rea

Although 900,000 of the men in U.S prisons are white, incarceration is treated as a Black problem, says Chicago-based sociologist and criminologist Reuben Jonathan Miller. Society still conflates Blackness with criminality, Miller told a UC Santa Barbara audience recently.

Miller was hosted by UCSB’s Interdisciplinary Humanities Center to discuss his research into incarcerated people and their families, in a recent Zoom webinar.

Criminologist and University of Chicago professor Reuben Jonathan Miller, right, explains the struggles that follow a loved one's incarceration while speaking on his book Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration with UCSB students . The virtual event was translated by ASL interpreter Katie Voice, left.

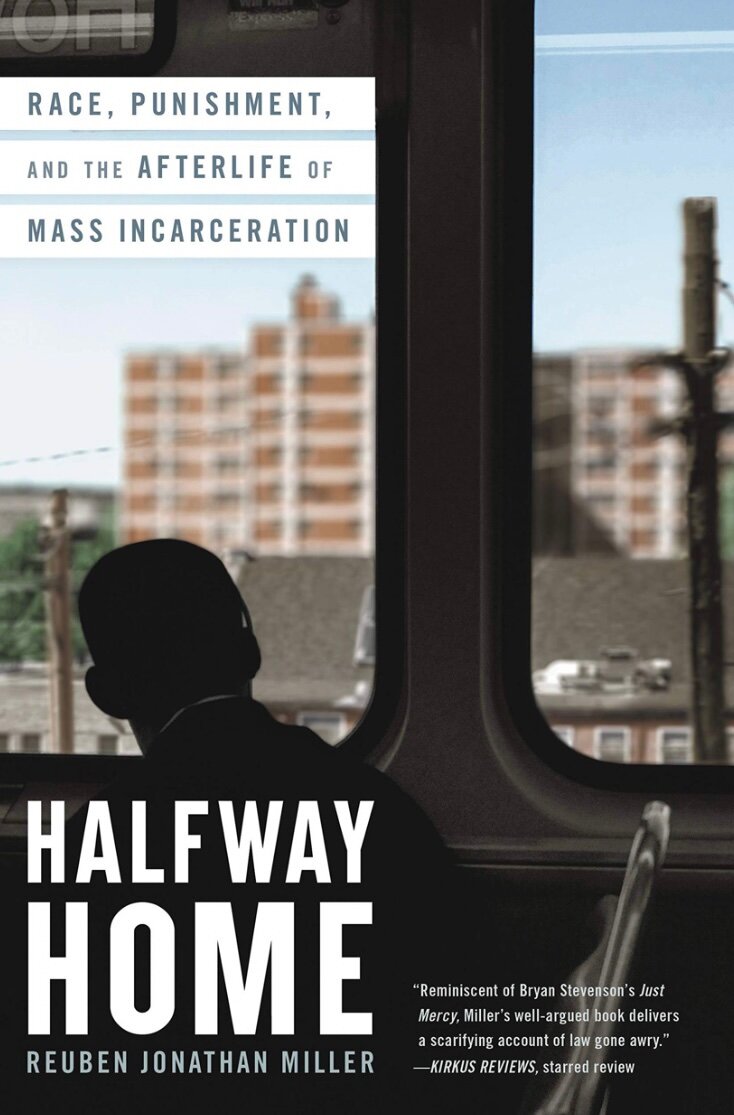

Miller, who teaches at the University of Chicago’s school of service administration, read emotionally charged excerpts from his book, Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration.

The book is based on 15 years of research into incarcerated individuals and is written in a narrative nonfiction style in which Miller takes the reader on an emotional journey while recounting the experiences of imprisoned men and women and the hardships of their family members.

“When you distance yourself from the emotions you are feeling, you miss things. Allowing myself to be close to the people I study, and to be honest about why I am here, gives me a perspective that other social scientists do not have,” Miller said.

To illustrate the trials that families endure, Miller described taking care of his own brother Jeremiah, who was incarcerated at a young age,

Sociologist and criminologist Reuben Jonathan Miller’s book Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration. The book is based on 15 years of research into imprisoned individuals.

“The court date you didn't have the gas money to attend. The conversations with your children about why their uncle was in prison. The $2.95 processing fee that overdrew your account. The unexpected embarrassment as you sit at your desk and order 30 packages of ramen noodles,” Miller recounted. “It's these little things that manage to put you down.”

Miller says the way communities view those who have completed their sentences is wrong. He believes that all criminals who have completed their time — not just those who went to jail for petty crimes — should be allowed to return to society without being seen as outcasts . These people who are “hard to love,” still have a place in society.

“We have to view people with criminal records as if they are fully human,” said Miller. “One thing I was confronted with in this work is what do we do with people who cause us harm. People who are hard to love. People who are hard to imagine having a place in the social world.”

Miller encourages society to recognize that there is much more to the incarcerated individual than crime they were accused of.

He commented on the court system, saying plea deals often force potentially innocent people to take a deal with limited prison time.

“We have gotten it wrong for so long, about how guilt and innocence works in this country. There have been 2,800 exonerations since 1989,” Miller said. “Ninety-five percent of these convictions are plea deals, which means the court does not have enough evidence to convict you. So they force you to take a deal by putting a worse one in front of you.”

Micah Rea is a third-year UC Santa Barbara student majoring in Communication. He wrote this article for his Writing Program class, Journalism for Web and Social Media.