By Amelia Faircloth

On January 6, 2021, when an armed mob stormed the U.S. capitol building to prevent Congress from verifying the presidential election, many viewers were shocked to see rioters sporting Christian symbols —"Jesus Saves" flags, wooden crosses, and Christian Bibles.

But for author and Oklahoma State University sociology professor Samuel Perry, the Christian symbols at the insurrection were not a surprise. Rather, they were the result of a growing prevalence of white Christian nationalism in American politics.

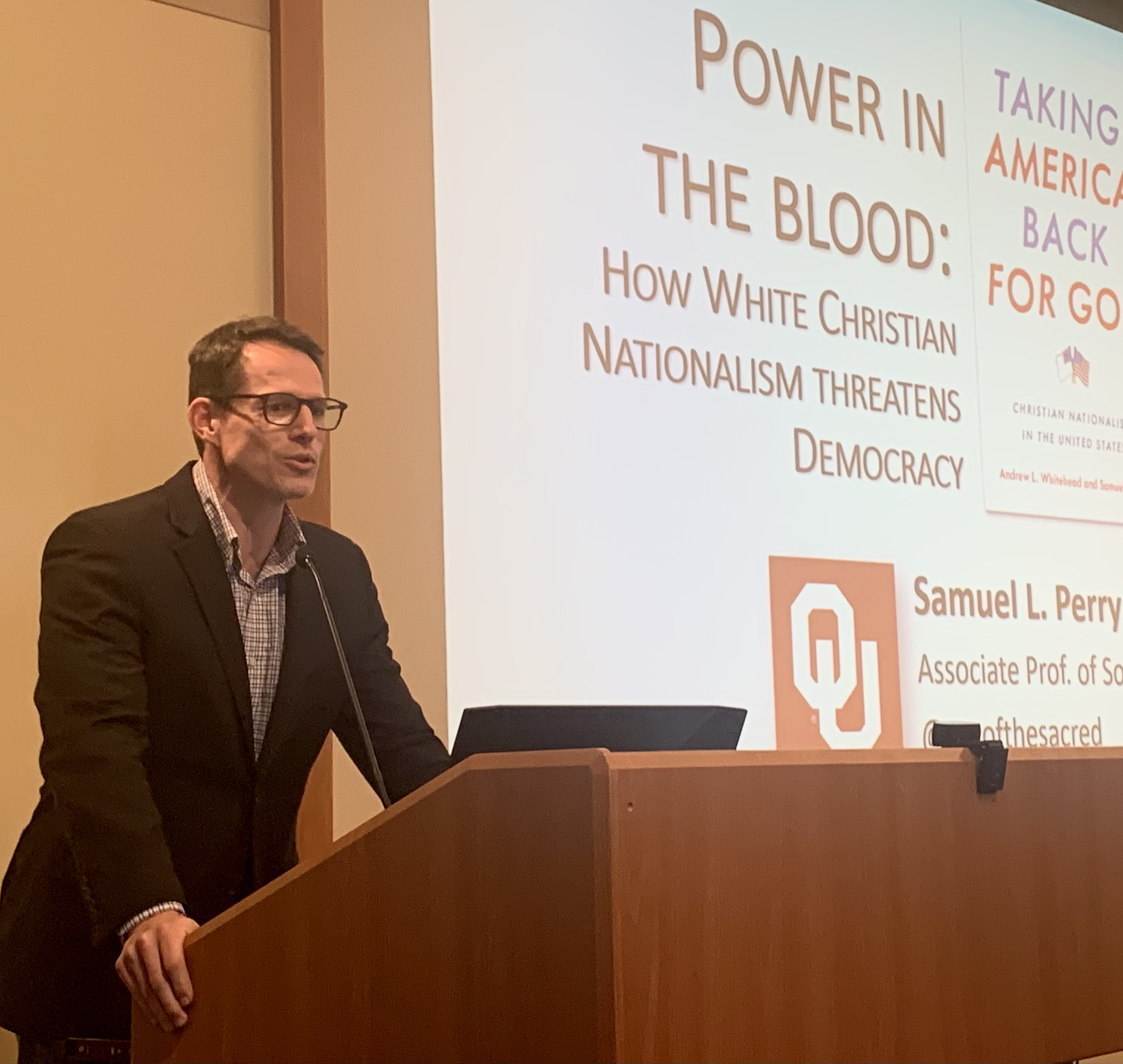

Oklahoma State University sociology professor Samuel Perry, presented his talk “Power in the Blood: How White Christian Nationalism Threatens Our Democracy.”

"White Christian nationalism is an ideology that demonstrably shapes political attitudes, and behavior," Perry told a UC Santa Barbara audience. "But white Christian nationalism can also be a political strategy that can be deployed, especially among white Christian audiences."

At the event, co-sponsored by UCSB Religious Studies and the Walter H. Capps Center, Perry presented research from national surveys and findings outlined in his newest book co-authored with Philip Gorski, “The Flag and the Cross,” to illuminate the threat white Christian nationalism poses to U.S democracy.

Christian nationalism refers to the belief that America is and always will be a Christian nation developed under Christian values. But, it was not until recently that the concept has been applied so explicitly in the political arena, he asserts.

Since 2014, Perry and his research partners have been measuring and defining Christian nationalist ideology through surveys. By asking Americans questions such as "Should the federal government declare the United States a Christian nation?" and "[Do you believe] the success of the United States is part of God's plan?” Perry has found that roughly 20 percent of Americans subscribe to these views.

In his research, Perry tries to avoid using titles such as "Christian nationalist," as he believes it creates more division than it alleviates. "It's like calling somebody a fascist, or calling somebody a Nazi," Perry explained. "It immediately shuts down conversation and we can't really have a productive conversation about this ideology." Instead, Perry opts for the phrase "Americans or white Americans who affirm Christian nationalist ideology."

Perry recognizes that Christian nationalists are not a single group, but rather that Christian nationalism is a belief system that exists on a spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is what Perry calls the "ambassadors," people who strongly agree with white Christian nationalist values. Those on the other end Perry calls "rejectors," representing the Americans who strongly disapprove of the ideology.

In a talk co-sponsored by UCSB Religious Studies and the Walter H. Capps Center, sociologist Samuel Perry explained how white Christian nationalism is increasingly used as a political device.

While the extreme ends of the spectrum account for about one-fifth of the population each, Perry says that most Americans fall somewhere in the middle.

"It seems that most Americans are kind of ambivalent with this ideology," Perry said. "Probably because most Americans are [Christian], or are at least on friendly terms with Christianity and Christian culture."

Though a majority of Americans neither overtly approve nor disapprove of Christian nationalism, the numbers of those who support the ideology are trending upwards.

"In this meta-analysis, we are seeing that an interest in Christian nationalism as a concept is increasing," Perry said.

Perry associates this increase, in part, with Donald Trump's use of Christian nationalism as a political strategy.

"It is only recently that presidents, specifically with the presidency of Donald Trump, activated explicitly Christian nationalist, Islamophobic rhetoric," Perry said.

Political leaders have historically used "civic religion" to encourage Americans to act morally and take accountability, Perry explained. The goal was to express religion in more secular terms to create unity among Americans. The recent use of explicitly Christian nationalist rhetoric, on the other hand, has the opposite effect.

One of Perry’s collaborators, Ceri Hughes at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has looked at the speeches and tweets of past American presidents and analyzed how frequently each president used words associated with faith, God, and Islam per 1000 words.

In a recent UCSB talk Samuel Perry outlined in his newly released book, "The Flag and The Cross: White Christian Nationalism and The Threat to American Democracy."

He discovered that Trump was far more likely than any previous president to use faith terms and God terms per 1000 words.

Hughes also looked at the types of words that would come before or after certain keywords. He found that Trump was more likely than any other president to associate Islam with words such as “victims,” “attack,” and “terrorists.” The use of these words connects Islam to racial terrorism and stokes fear among Christian Americans, Perry explained. Trump associated Muslims with enabling violence in roughly 77 % of the times he mentioned Islam.

"Trump is unlike every other president in the way that he associated Islam with violence, unlike every other president since [Jimmy] Carter, who almost always when referencing Islam talked about Muslims as opposing violence.”

The use of religion in this way gives people who believe in Christian nationalist ideas the impression that Christianity, and thus American culture, are under attack.

Perry argues this has caused harm by racializing Christianity and Christian values. When politicians emphasize Christian values or claim that Christian values are under attack, "they can actually trigger unconsciously or subconsciously or subliminally, the perception on white Christians that whites themselves are under attack."

Perry’s research on Christian nationalism as an ideology has become the standard for researching this area in sociology and political science. But he feels that looking into the role of Christian nationalism as a political driver is even more urgent.

“As much research as we have done on Christian nationalism as an ideology, I think the [research area] that is emerging on Christian nationalism as a political strategy is becoming emergently relevant and even a little bit scarier than the former,” Perry said.

Amelia Faircloth is a fourth-year UC Santa Barbara student majoring in English. She is a Web and Social Media Intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.