UCSB English professor Kenneth Hiltner was named a 2022 recipient of the Distinguished Teaching Award due to the positive impact his Ecocriticism and climate crisis courses have on the community.

By Makenna Gaeta and Sophie Ludgin

UC Santa Barbara English professor Kenneth Hiltner was recently named a 2022 recipient of the Distinguished Teaching Award. The award reflects the highest standard of teaching excellence, recognizing six faculty members’ efforts to enhance the educational experience of UCSB students. Awardees are selected via student and faculty nomination, receiving a cash award of $1000 and a framed certificate.

Hiltner, a professor of Environmental Humanities, is using his scholarship to change the way people think about the environment— and it’s working.

“It’s a cultural thing. It’s a human thing. The humanities and social sciences have a big contribution to make.”

With an extensive background in farming and woodwork, Hiltner has always been interested in environmentalism. After graduating with a Ph.D. in English from Harvard, Hiltner stayed in academics to educate college students about human-caused climate change. He writes and teaches his courses through a lens of culture and literature, stressing the humanities— not just science— within the conversation about our planet’s future.

Hiltner’s impact on campus is far-reaching, as the popularity of his Ecocriticism course and climate crisis courses in the English Department completely fill Campbell Hall’s 800 seats.

We sat down with Hiltner to discuss the evolution of his academic career, the human component of global climate change, and his recent award recognition.

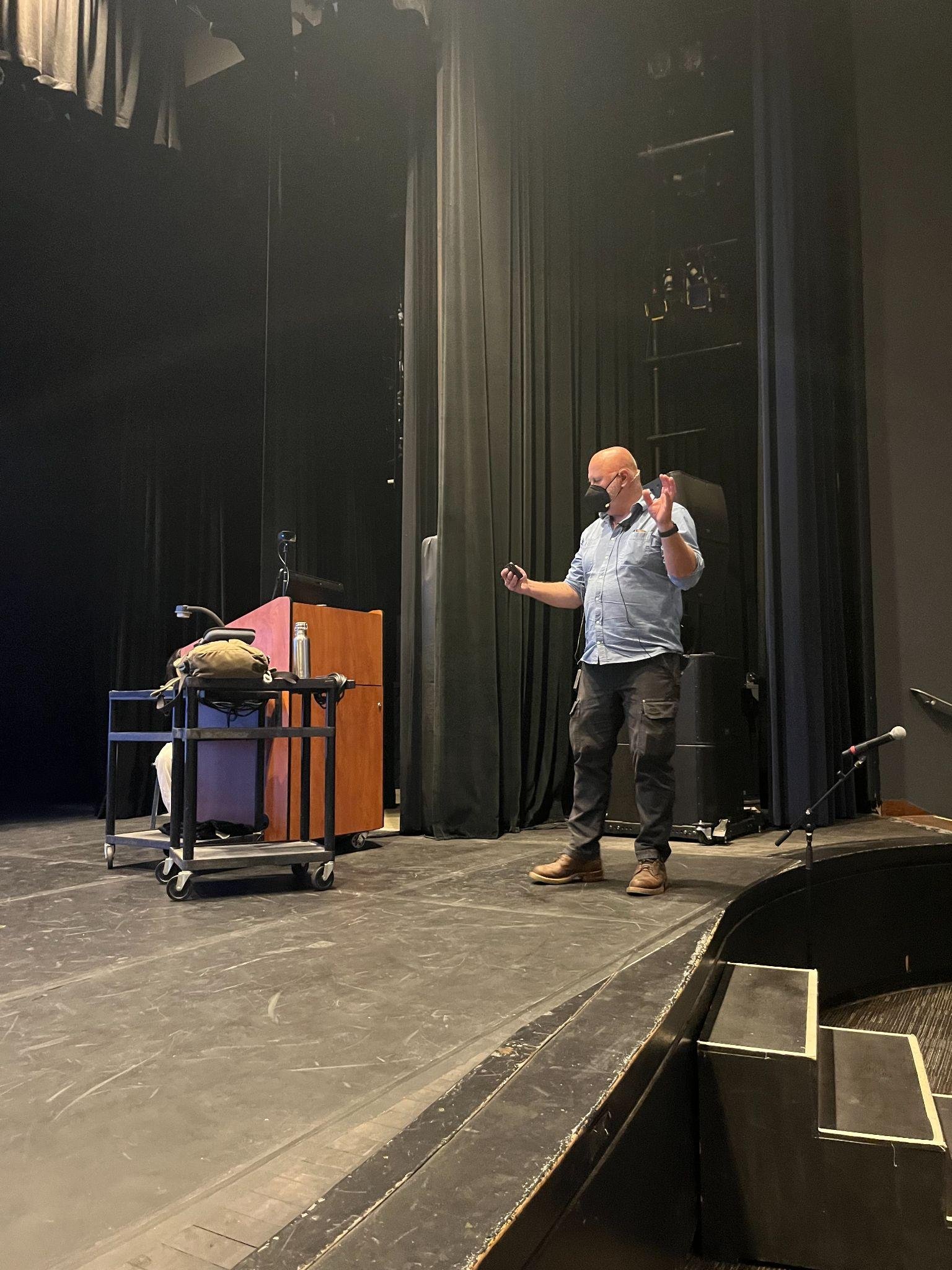

Environmental Humanities professor Kenneth Hiltner lectures to his Climate Crisis 101 class, a course offered by the English department.

Q: You have had a highly accomplished academic career, graduating from Harvard University with a number of distinctions. What was your educational journey like before pursuing your Ph.D.?

A: I'm actually seriously dyslexic, and I was a horrible student in high school. I went to a local community college and it took me 14 years to get my undergraduate degree. I was 32 at that time, and then I went and got a master's degree at Rutgers. I had a 2.7 GPA. So, none of this would have gotten me into Harvard if you do the math. But I wrote a very long master's thesis that was published as a book by Cambridge University Press, which is the most respected press in my field. Once I had that published, I then applied to a number of schools, and I got in everywhere. So, I decided to go to Harvard.

Q: How have your views regarding the environment evolved since becoming a professor at UCSB?

A: I came to realize that the urgency of the climate crisis requires speaking to the public in a way that scholars don’t. Scholars spend a lot of time talking to each other and then over time— and that could be even decades later— it breaks out into the public knowledge. We need to get the word out immediately, which is why my scholarship has turned more towards educating the public. And one of the good things about [these courses] is that we set up YouTube channels for all of them. People share this information with their friends or with high school teachers and it gets disseminated more broadly.

Environmentalist Kenneth Hiltner’s Climate Crisis class is held in UC Santa Barbara’s Campbell Hall, filling 800 seats with interested students.

Q: Your courses honor the intersection between literature and science in tackling the climate crisis. Why is it important to incorporate humanities into the dialogue about the environment?

A: When you think about the kind of intervention that we need to do environmentally, you think it's going to be science, right? It's going to be a newer generation of solar cells or lithium-ion batteries for electric cars. But if you look at the interventions, what's really needed are things like educating girls and giving them access to family planning. The more education a woman has, the fewer children she has, which has huge environmental gains. It's a cultural thing. It's a human thing. And that's where I think the humanities and social sciences together have a big contribution to make. I'm not saying that the natural sciences aren’t great too but they’re not the whole story.

Q: Following up on that, do you believe that there should be more of a balance between scientific and literature-based explanations for climate change in media coverage?

A: I think so. One of the issues is that people in general sort of hope that applied science is going to solve the problem for us. If you shift away from thinking about just solving this technologically, then you'll come back to a cultural issue. It’s going to require a change in the way we do things. And that’s where I think the media could come in to help with that.

Q: You were recently presented with UCSB’s Distinguished Teaching Award during your Climate Crisis 101 lecture. Can you give us details about this award?

A: Each year it is given to one or more UCSB faculty for their teaching and it's great because it's entirely student-driven. As a professor, I write tons of letters of recommendation for people. But in this case, it's students writing letters of recommendation for me. So it was very rewarding to receive that. At this point in my career, I've written four books, edited three more, and have another one in the works. So, I've kind of done that. A lot of that. To me, teaching is now the most important part of the way, I think.

Makenna Gaeta and Sophie Ludgin are both second-year Communication majors at UCSB. They co-wrote this Q&A for their Writing Program course Digital Journalism.