By Ryan Monasch

Artist and UCLA photography professor Rodrigo Valenzuela.

Chilean-born artist Rodrigo Valenzuela says visual art acts as an important autobiographical and storytelling mechanism. “You have the right to make whatever you want with the things that inspire you,” Valenzuela told a UC Santa Barbara audience.

Valenzuela was hosted by UCSB’s Art Department as part of its Visiting Artist Speaker Series. He spoke to art students and faculty about his journey as an artist and advocate, describing his creative evolution, and the inspirations behind his work.

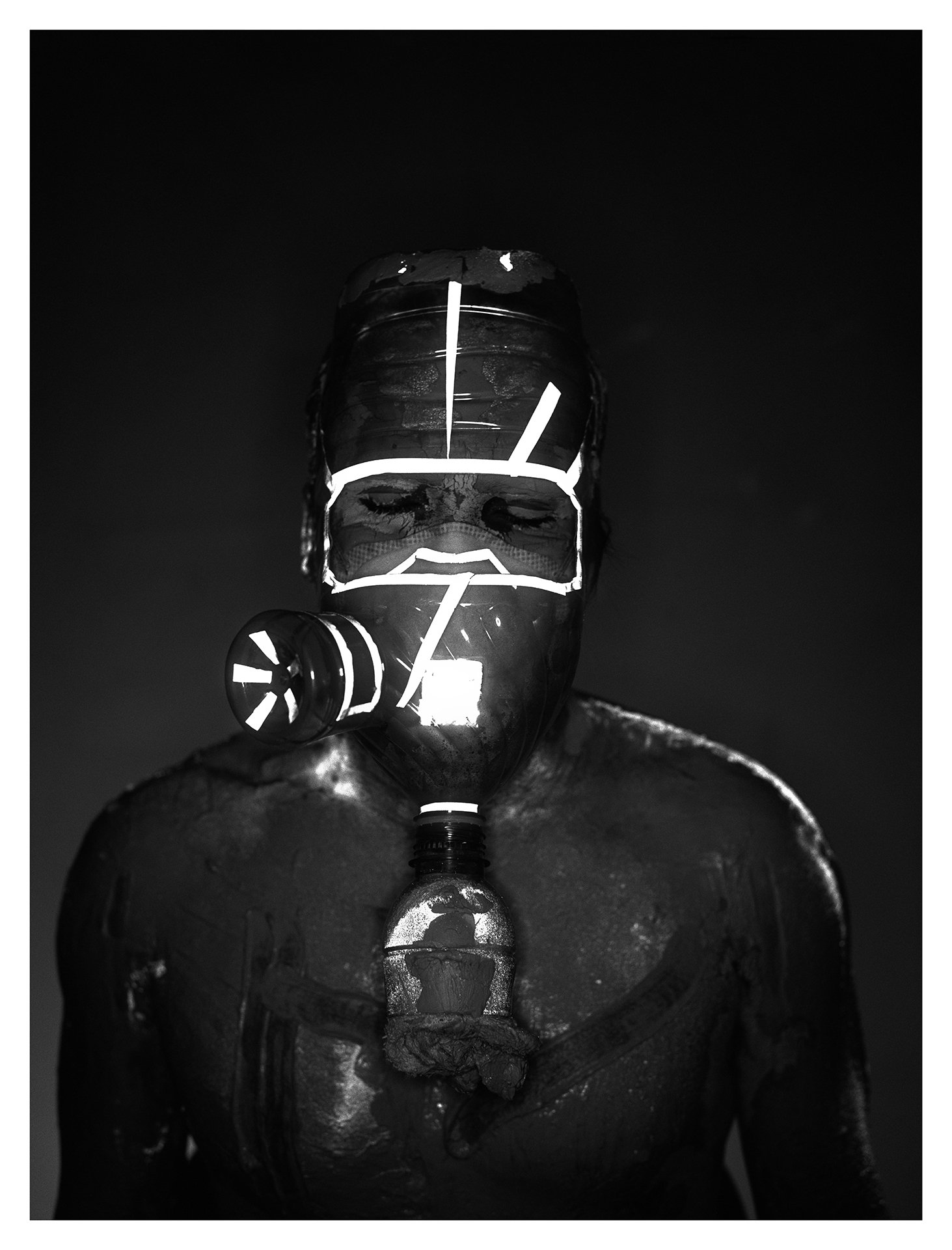

Artist Rodrigo Valenzuela’s piece titled “Stature No. 5” from his Stature series.

Currently a professor at UCLA, Valenzuela works with photography, videography, and sculpture to construct narratives based on tensions among individuals and their communities, often delving into topics such as immigration and invisible labor. As a multimedia artist, he works primarily with photography, often consisting of images that include sculptures made of various materials like clay, wood, Styrofoam, and concrete. His 2020 collection titled Stature uses images of sculptures made of Styrofoam that he found in trash cans around downtown Los Angeles.

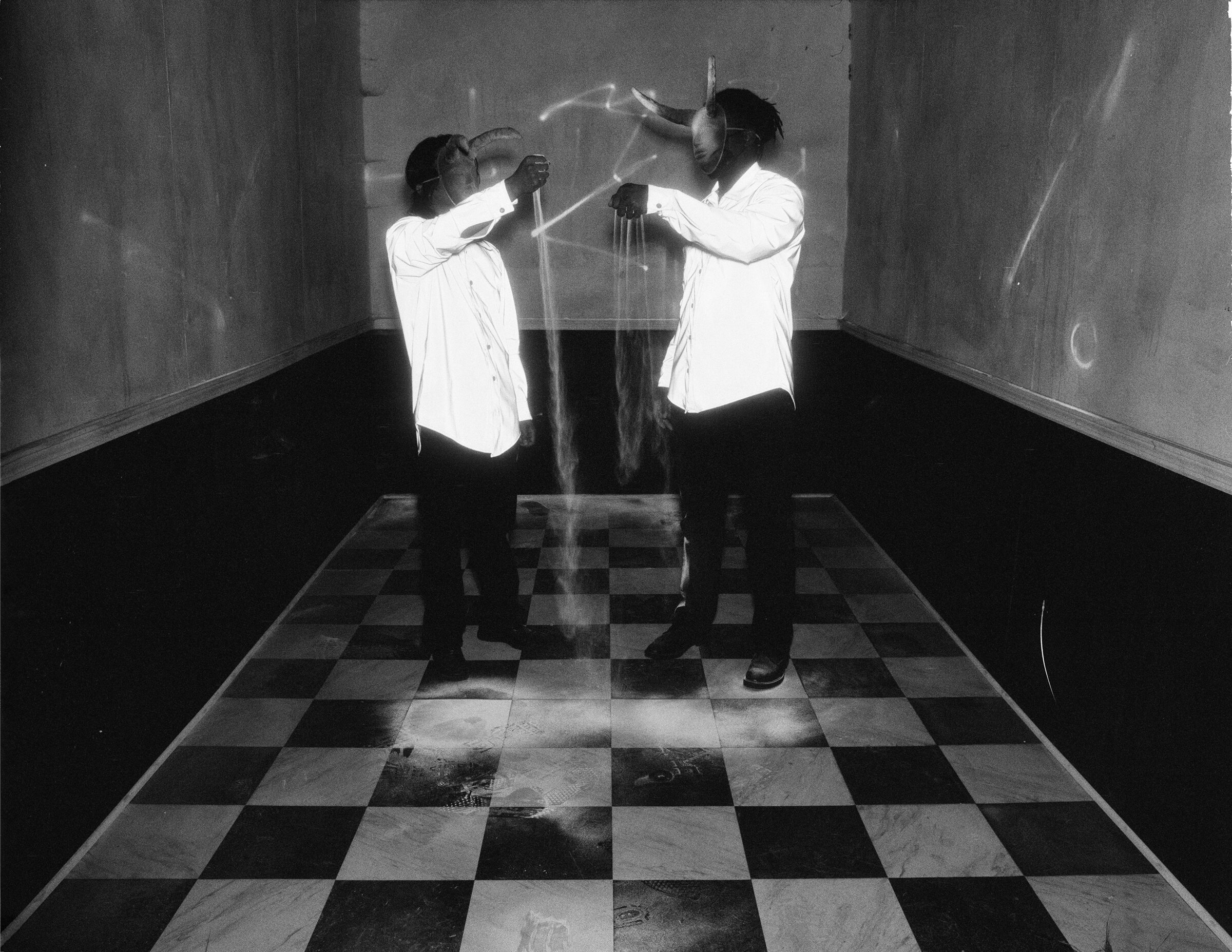

Valenzuela also turns to filmmaking, creating videos that tell stories of working-class individuals and people of color. One of his videography works takes on the racial bias in facial recognition technology. In it a single white person stands amid people of color, while a camera continuously attempts to focus on everyone around, yet only detects the white face in the middle.

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s video titled Tertiary.

The photography professor began his speech by describing his move from Chile to Canada when he was 21 years old and his subsequent years working in construction there. Seeking a deeper understanding of his craft, he pursued a BA in philosophy at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington in 2010, and an MFA in philosophy at the University of Seattle, Washington in 2012.

“I tried to make art but always felt like I needed something else so I went to study philosophy. I always believed artists to be super smart,” said Valenzuela. He sought to become a “smart artist,” but still grappled with the complexity of creating authentic art in the environment he found himself in.

Valenzuela finally found an encouraging space for his artistic exploration in a residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Culture in Maine, where he was surrounded by mentors and fellow artists with diverse practices. “I went to Skowhegan and it blew my mind. I met 60 or 70 artists, and they all had a different practice. I had mentors, teachers, and I had a studio,” said Valenzuela. He described finding a new freedom in a studio environment.

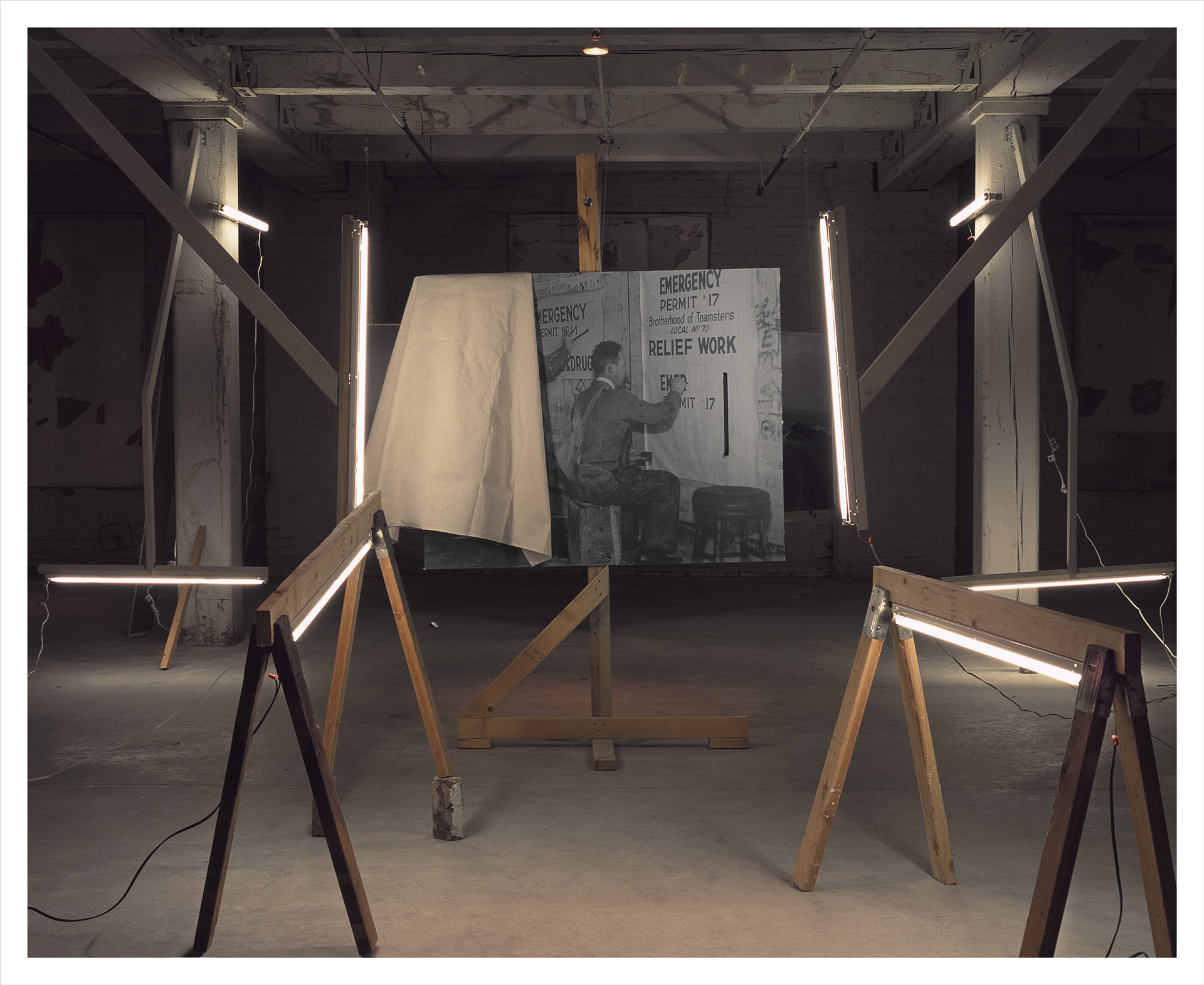

Making art with materials connected to his background in construction constituted a pivotal moment in his creative journey. “I do have a lot of experience in construction, I worked most of my 20s, working on concrete, and carpentry. I worked with a lot of moving companies. All things that now come more in handy than ever,” he said.

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s photography piece titled “The Builder No. 3” from his series, The Builder.

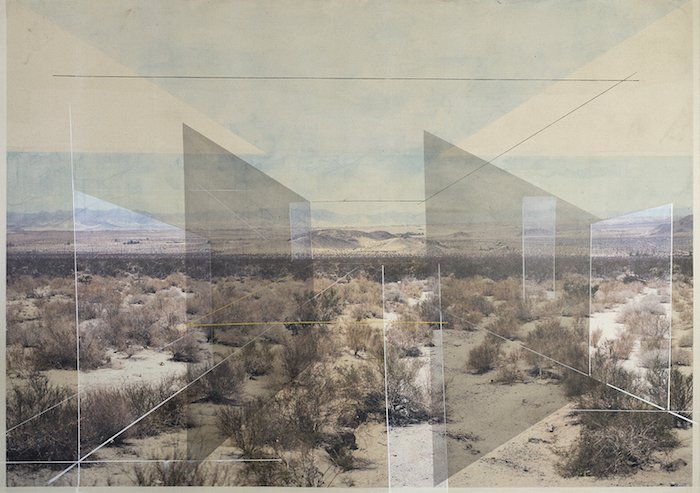

The artist began to focus on landscapes in 2012, portraying places of desire that were uninhabited, such as mountains and deserts—a reflection of his experiences as an immigrant in various cities across the United States. He became a U.S. citizen following 18 years as an undocumented immigrant and decided to use photocopies in his landscape artwork, as material to represent bureaucracy’s impact on immigrants.

“That is why I wanted to make a lot of photocopies because, through my experience, the idea of being an immigrant is more connected to paperwork.” Valenzuela sees immigration paperwork as a never-ending process. “That’s how you wear out the poor and the immigrants, by overwhelming them with paperwork, by making it feel impossible to survive the system,” he said.

Valenzuela also focuses on labor unions, invisible labor, and the idea of ruins and monuments. In one art project on labor unions he created flags with union logos on them to portray collectivism within the life of the working class.

Another project was a Chilean telenovela titled “Maria TV,” inspired by his childhood in which he was raised by his grandmother, mother, aunt, and sister. The film features a group of Chilean working women, some in casual clothes, and some in housekeeping outfits, speaking on their varying female experiences. Another category of work is his creation of public altars. “I made an installation that acts as a memorial site where people can honor their deceased loved ones. They have all of the qualities of a monument without all of the historical issues,” he said.

A telenovela by Rodrigo Valenzuela titled Maria TV.

Some of Valenzuela’s more recent work explores political protest, drawing on experience both in Chile when he was growing up during the transition to democracy and in public protests within the United States. In this artwork, he incorporates barricades covered in clay to represent the aesthetic of protests as a byproduct of capitalism.

He believes that capitalism should not be involved in social movements, for example, vendors selling pink hats during the women’s march in 2017. He says that barricades, often made out of palettes that are used to transport goods, act as a powerful portrayal of capitalism when they are used as barriers against protestors during political rebellions.

Valenzuela left the audience with an encouraging message about how his love for learning drove him as an artist and prompted him to put so much thought and effort into the research behind his creative work. “It may be because I have an insecurity of not being talented enough, but sometimes your insecurities are your greatest gift,” he said.

Click on the slide show, below, to see more work by Rodrigo Valenzuela.

Ryan Monasch is a third-year UCSB student, majoring in Film and Media Studies. She is a Web and Social Media intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.